“I’m sorry,” the words trickled from my mouth, as I gazed at my father’s coffin. These are not words I thought or intended to say, they came from a wellspring deep inside of me, surprising me in many ways but in some ways not. He appeared uncharacteristically sophisticated wearing a navy-blue blazer and tie. He looked like he found peace, after struggling with a body that outlived his mind.

“I’m sorry,” the words trickled from my mouth, as I gazed at my father’s coffin. These are not words I thought or intended to say, they came from a wellspring deep inside of me, surprising me in many ways but in some ways not. He appeared uncharacteristically sophisticated wearing a navy-blue blazer and tie. He looked like he found peace, after struggling with a body that outlived his mind.

I was sorry for how our family turned out. Like many families, we were broken. When you are part of this kind of family, you see the outside as perfect, families enveloped in two-story homes, with adoring parents and a pet or two. We were broken by fate, illness, bad luck – you choose. It wasn’t the first time, death arrived unannounced like a thunderstorm in early summer, just when you start to exhale and enjoy long evenings outdoors filled with fireflies and you feel all is good with the world.

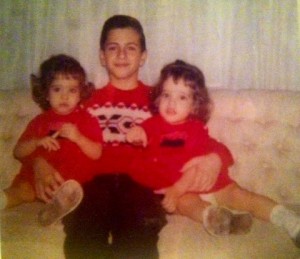

I was sorry for our losses. This story began with my mother. She was young and radiant growing up as a teen in the 40s, talented and creative. Her aspirations curtailed by society’s expectations and money or lack thereof. She was engaged to a dashing young man, who shared her creativity and passion. She didn’t know, he had an unrepairable heart condition that would leave her widowed with a three-year-old son. Enter my father, waiting for the one. Overjoyed by his great fortune, he married my mother. This was a family of three, then five with the birth of my twin sister and I. Eleven short years, tragedy struck, and my mother was taken by breast cancer. We became a family of four, then three as my brother packed his grief for his own adventures.

I was sorry for all of us. Truth is we weren’t very particularly good at this family of three. There were no playbooks in the 70s on how a man raises two 11-year-old girls. He was lost to us as well, mired in grief. We were like weeds but obedient ones, walking to school, coming home, and doing homework. Most of the familial duties I carried on for my own family were non-existent. Dinner was what my grandmother would make but that didn’t last long. Then dinner was what we could pick up, go out for, and figure out by opening a can of tuna. I learned to cook.

I’m sorry that I couldn’t fix what was wrong or change anything. Yet, I tried. I wanted to make my father happy, the last parent standing. I tried my entire life, and true to my Catholic upbringing I fought hard to make him happy with an unwavering commitment with no endgame or victory in sight. I dodged his moods. I wanted happiness more for him than for myself. I failed.

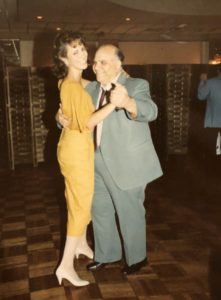

I’m sorry for feeling the way I did. He was a mix of the most entertaining person in the room to the surliest. You didn’t know what you would get, like cereal boxes or Cracker Jacks, hoping you would find a prized toy but knowing it would be one of the same toys you have plenty of. I loved his entertaining and personable side, ready to converse with anyone and loving all kinds of new friends. I hoarded those times. I loved the jelly donuts he would buy on Sunday mornings and how his warm hugs felt safe.

I’m sorry that when we grew up and left home, he struggled to find a sense of who he was. I carried Catholic guilt the size of a tractor-trailer. The yin and yang of trying to enjoy my accomplishments with the gnawing wonder of how I can enjoy anything while he was unhappy.

I’m not sorry for loving him or for what he taught me. That people are not perfect, that change is hard and sometimes people don’t desire change. That people are complicated and sometimes their best intentions never get off the ground. In the end, most people do the best they can with what they have. I believe that about my father. The only sorry I hold now is I’m sorry he is gone.